Speeding up Linux disk encryption

This is a repost of my post from the Cloudflare Blog

Data encryption at rest is a must-have for any modern Internet company. Many companies, however, don’t encrypt their disks, because they fear the potential performance penalty caused by encryption overhead.

Encrypting data at rest is vital for Cloudflare with more than 200 data centres across the world. In this post, we will investigate the performance of disk encryption on Linux and explain how we made it at least two times faster for ourselves and our customers!

Encrypting data at rest

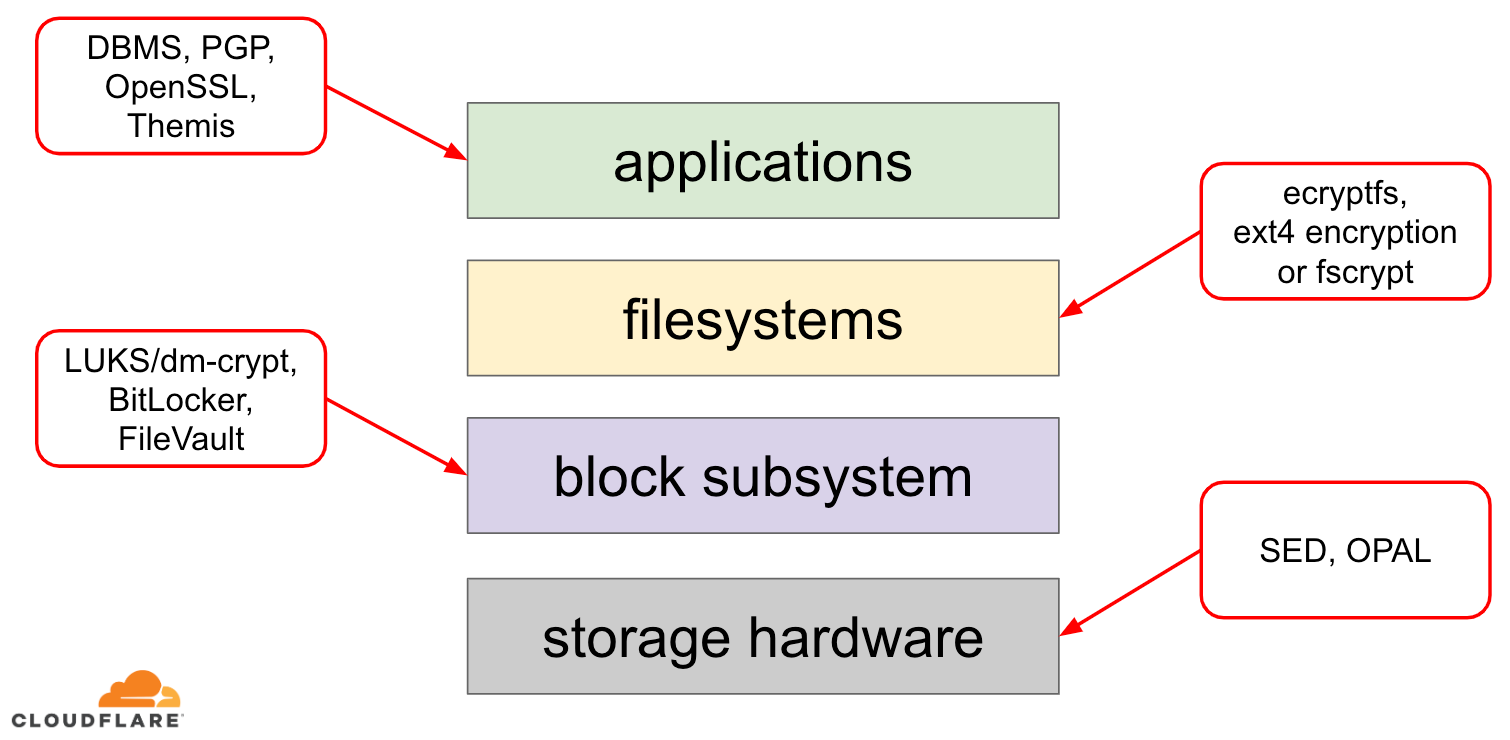

When it comes to encrypting data at rest there are several ways it can be implemented on a modern operating system (OS). Available techniques are tightly coupled with a typical OS storage stack. A simplified version of the storage stack and encryption solutions can be found on the diagram below:

On the top of the stack are applications, which read and write data in files (or streams). The file system in the OS kernel keeps track of which blocks of the underlying block device belong to which files and translates these file reads and writes into block reads and writes, however the hardware specifics of the underlying storage device is abstracted away from the filesystem. Finally, the block subsystem actually passes the block reads and writes to the underlying hardware using appropriate device drivers.

The concept of the storage stack is actually similar to the well-known network OSI model, where each layer has a more high-level view of the information and the implementation details of the lower layers are abstracted away from the upper layers. And, similar to the OSI model, one can apply encryption at different layers (think about TLS vs IPsec or a VPN).

For data at rest we can apply encryption either at the block layers (either in hardware or in software) or at the file level (either directly in applications or in the filesystem).

Block vs file encryption

Generally, the higher in the stack we apply encryption, the more flexibility we have. With application level encryption the application maintainers can apply any encryption code they please to any particular data they need. The downside of this approach is they actually have to implement it themselves and encryption in general is not very developer-friendly: one has to know the ins and outs of a specific cryptographic algorithm, properly generate keys, nonces, IVs etc. Additionally, application level encryption does not leverage OS-level caching and Linux page cache in particular: each time the application needs to use the data, it has to either decrypt it again, wasting CPU cycles, or implement its own decrypted “cache”, which introduces more complexity to the code.

File system level encryption makes data encryption transparent to applications, because the file system itself encrypts the data before passing it to the block subsystem, so files are encrypted regardless if the application has crypto support or not. Also, file systems can be configured to encrypt only a particular directory or have different keys for different files. This flexibility, however, comes at a cost of a more complex configuration. File system encryption is also considered less secure than block device encryption as only the contents of the files are encrypted. Files also have associated metadata, like file size, the number of files, the directory tree layout etc., which are still visible to a potential adversary.

Encryption down at the block layer (often referred to as disk encryption or full disk encryption) also makes data encryption transparent to applications and even whole file systems. Unlike file system level encryption it encrypts all data on the disk including file metadata and even free space. It is less flexible though - one can only encrypt the whole disk with a single key, so there is no per-directory, per-file or per-user configuration. From the crypto perspective, not all cryptographic algorithms can be used as the block layer doesn’t have a high-level overview of the data anymore, so it needs to process each block independently. Most common algorithms require some sort of block chaining to be secure, so are not applicable to disk encryption. Instead, special modes were developed just for this specific use-case.

So which layer to choose? As always, it depends… Application and file system level encryption are usually the preferred choice for client systems because of the flexibility. For example, each user on a multi-user desktop may want to encrypt their home directory with a key they own and leave some shared directories unencrypted. On the contrary, on server systems, managed by SaaS/PaaS/IaaS companies (including Cloudflare) the preferred choice is configuration simplicity and security - with full disk encryption enabled any data from any application is automatically encrypted with no exceptions or overrides. We believe that all data needs to be protected without sorting it into “important” vs “not important” buckets, so the selective flexibility the upper layers provide is not needed.

Hardware vs software disk encryption

When encrypting data at the block layer it is possible to do it directly in the storage hardware, if the hardware supports it. Doing so usually gives better read/write performance and consumes less resources from the host. However, since most hardware firmware is proprietary, it does not receive as much attention and review from the security community. In the past this led to flaws in some implementations of hardware disk encryption, which render the whole security model useless. Microsoft, for example, started to prefer software-based disk encryption since then.

We didn’t want to put our data and our customers’ data to the risk of using potentially insecure solutions and we strongly believe in open-source. That’s why we rely only on software disk encryption in the Linux kernel, which is open and has been audited by many security professionals across the world.

Linux disk encryption performance

We aim not only to save bandwidth costs for our customers, but to deliver content to Internet users as fast as possible.

At one point we noticed that our disks were not as fast as we would like them to be. Some profiling as well as a quick A/B test pointed to Linux disk encryption. Because not encrypting the data (even if it is supposed-to-be a public Internet cache) is not a sustainable option, we decided to take a closer look into Linux disk encryption performance.

Device mapper and dm-crypt

Linux implements transparent disk encryption via a dm-crypt module and dm-crypt itself is part of device mapper kernel framework. In a nutshell, the device mapper allows pre/post-process IO requests as they travel between the file system and the underlying block device.

dm-crypt in particular encrypts “write” IO requests before sending them further down the stack to the actual block device and decrypts “read” IO requests before sending them up to the file system driver. Simple and easy! Or is it?

Benchmarking setup

For the record, the numbers in this post were obtained by running specified commands on an idle Cloudflare G9 server out of production. However, the setup should be easily reproducible on any modern x86 laptop.

Generally, benchmarking anything around a storage stack is hard because of the noise introduced by the storage hardware itself. Not all disks are created equal, so for the purpose of this post we will use the fastest disks available out there - that is no disks.

Instead Linux has an option to emulate a disk directly in RAM. Since RAM is much faster than any persistent storage, it should introduce little bias in our results.

The following command creates a 4GB ramdisk:

$ sudo modprobe brd rd_nr=1 rd_size=4194304

$ ls /dev/ram0

Now we can set up a dm-crypt instance on top of it thus enabling encryption for the disk. First, we need to generate the disk encryption key, “format” the disk and specify a password to unlock the newly generated key.

$ fallocate -l 2M crypthdr.img

$ sudo cryptsetup luksFormat /dev/ram0 --header crypthdr.img

WARNING!

========

This will overwrite data on crypthdr.img irrevocably.

Are you sure? (Type uppercase yes): YES

Enter passphrase:

Verify passphrase:

Those who are familiar with LUKS/dm-crypt might have noticed we used a LUKS detached header here. Normally, LUKS stores the password-encrypted disk encryption key on the same disk as the data, but since we want to compare read/write performance between encrypted and unencrypted devices, we might accidentally overwrite the encrypted key during our benchmarking later. Keeping the encrypted key in a separate file avoids this problem for the purposes of this post.

Now, we can actually “unlock” the encrypted device for our testing:

$ sudo cryptsetup open --header crypthdr.img /dev/ram0 encrypted-ram0

Enter passphrase for /dev/ram0:

$ ls /dev/mapper/encrypted-ram0

/dev/mapper/encrypted-ram0

At this point we can now compare the performance of encrypted vs unencrypted ramdisk: if we read/write data to /dev/ram0, it will be stored in plaintext. Likewise, if we read/write data to /dev/mapper/encrypted-ram0, it will be decrypted/encrypted on the way by dm-crypt and stored in ciphertext.

It’s worth noting that we’re not creating any file system on top of our block devices to avoid biasing results with a file system overhead.

Measuring throughput

When it comes to storage testing/benchmarking Flexible I/O tester is the usual go-to solution. Let’s simulate simple sequential read/write load with 4K block size on the ramdisk without encryption:

$ sudo fio --filename=/dev/ram0 --readwrite=readwrite --bs=4k --direct=1 --loops=1000000 --name=plain

plain: (g=0): rw=rw, bs=4K-4K/4K-4K/4K-4K, ioengine=psync, iodepth=1

fio-2.16

Starting 1 process

...

Run status group 0 (all jobs):

READ: io=21013MB, aggrb=1126.5MB/s, minb=1126.5MB/s, maxb=1126.5MB/s, mint=18655msec, maxt=18655msec

WRITE: io=21023MB, aggrb=1126.1MB/s, minb=1126.1MB/s, maxb=1126.1MB/s, mint=18655msec, maxt=18655msec

Disk stats (read/write):

ram0: ios=0/0, merge=0/0, ticks=0/0, in_queue=0, util=0.00%

The above command will run for a long time, so we just stop it after a while. As we can see from the stats, we’re able to read and write roughly with the same throughput around 1126 MB/s. Let’s repeat the test with the encrypted ramdisk:

$ sudo fio --filename=/dev/mapper/encrypted-ram0 --readwrite=readwrite --bs=4k --direct=1 --loops=1000000 --name=crypt

crypt: (g=0): rw=rw, bs=4K-4K/4K-4K/4K-4K, ioengine=psync, iodepth=1

fio-2.16

Starting 1 process

...

Run status group 0 (all jobs):

READ: io=1693.7MB, aggrb=150874KB/s, minb=150874KB/s, maxb=150874KB/s, mint=11491msec, maxt=11491msec

WRITE: io=1696.4MB, aggrb=151170KB/s, minb=151170KB/s, maxb=151170KB/s, mint=11491msec, maxt=11491msec

Whoa, that’s a drop! We only get ~147 MB/s now, which is more than 7 times slower! And this is on a totally idle machine!

Maybe, crypto is just slow

The first thing we considered is to ensure we use the fastest crypto. cryptsetup allows us to benchmark all the available crypto implementations on the system to select the best one:

$ sudo cryptsetup benchmark

# Tests are approximate using memory only (no storage IO).

PBKDF2-sha1 1340890 iterations per second for 256-bit key

PBKDF2-sha256 1539759 iterations per second for 256-bit key

PBKDF2-sha512 1205259 iterations per second for 256-bit key

PBKDF2-ripemd160 967321 iterations per second for 256-bit key

PBKDF2-whirlpool 720175 iterations per second for 256-bit key

# Algorithm | Key | Encryption | Decryption

aes-cbc 128b 969.7 MiB/s 3110.0 MiB/s

serpent-cbc 128b N/A N/A

twofish-cbc 128b N/A N/A

aes-cbc 256b 756.1 MiB/s 2474.7 MiB/s

serpent-cbc 256b N/A N/A

twofish-cbc 256b N/A N/A

aes-xts 256b 1823.1 MiB/s 1900.3 MiB/s

serpent-xts 256b N/A N/A

twofish-xts 256b N/A N/A

aes-xts 512b 1724.4 MiB/s 1765.8 MiB/s

serpent-xts 512b N/A N/A

twofish-xts 512b N/A N/A

It seems aes-xts with a 256-bit data encryption key is the fastest here. But which one are we actually using for our encrypted ramdisk?

$ sudo dmsetup table /dev/mapper/encrypted-ram0

0 8388608 crypt aes-xts-plain64 0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000 0 1:0 0

We do use aes-xts with a 256-bit data encryption key (count all the zeroes conveniently masked by dmsetup tool - if you want to see the actual bytes, add the --showkeys option to the above command). The numbers do not add up however: cryptsetup benchmark tells us above not to rely on the results, as “Tests are approximate using memory only (no storage IO)”, but that is exactly how we’ve set up our experiment using the ramdisk. In a somewhat worse case (assuming we’re reading all the data and then encrypting/decrypting it sequentially with no parallelism) doing back-of-the-envelope calculation we should be getting around (1126 * 1823) / (1126 + 1823) =~696 MB/s, which is still quite far from the actual 147 * 2 = 294 MB/s (total for reads and writes).

dm-crypt performance flags

While reading the cryptsetup man page we noticed that it has two options prefixed with --perf-, which are probably related to performance tuning. The first one is --perf-same_cpu_crypt with a rather cryptic description:

Perform encryption using the same cpu that IO was submitted on. The default is to use an unbound workqueue so that encryption work is automatically balanced between available CPUs. This option is only relevant for open action.

So we enable the option

$ sudo cryptsetup close encrypted-ram0

$ sudo cryptsetup open --header crypthdr.img --perf-same_cpu_crypt /dev/ram0 encrypted-ram0

Note: according to the latest man page there is also a cryptsetup refresh command, which can be used to enable these options live without having to “close” and “re-open” the encrypted device. Our cryptsetup however didn’t support it yet.

Verifying if the option has been really enabled:

$ sudo dmsetup table encrypted-ram0

0 8388608 crypt aes-xts-plain64 0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000 0 1:0 0 1 same_cpu_crypt

Yes, we can now see same_cpu_crypt in the output, which is what we wanted. Let’s rerun the benchmark:

$ sudo fio --filename=/dev/mapper/encrypted-ram0 --readwrite=readwrite --bs=4k --direct=1 --loops=1000000 --name=crypt

crypt: (g=0): rw=rw, bs=4K-4K/4K-4K/4K-4K, ioengine=psync, iodepth=1

fio-2.16

Starting 1 process

...

Run status group 0 (all jobs):

READ: io=1596.6MB, aggrb=139811KB/s, minb=139811KB/s, maxb=139811KB/s, mint=11693msec, maxt=11693msec

WRITE: io=1600.9MB, aggrb=140192KB/s, minb=140192KB/s, maxb=140192KB/s, mint=11693msec, maxt=11693msec

Hmm, now it is ~136 MB/s which is slightly worse than before, so no good. What about the second option --perf-submit_from_crypt_cpus:

Disable offloading writes to a separate thread after encryption. There are some situations where offloading write bios from the encryption threads to a single thread degrades performance significantly. The default is to offload write bios to the same thread. This option is only relevant for open action.

Maybe, we are in the “some situation” here, so let’s try it out:

$ sudo cryptsetup close encrypted-ram0

$ sudo cryptsetup open --header crypthdr.img --perf-submit_from_crypt_cpus /dev/ram0 encrypted-ram0

Enter passphrase for /dev/ram0:

$ sudo dmsetup table encrypted-ram0

0 8388608 crypt aes-xts-plain64 0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000 0 1:0 0 1 submit_from_crypt_cpus

And now the benchmark:

$ sudo fio --filename=/dev/mapper/encrypted-ram0 --readwrite=readwrite --bs=4k --direct=1 --loops=1000000 --name=crypt

crypt: (g=0): rw=rw, bs=4K-4K/4K-4K/4K-4K, ioengine=psync, iodepth=1

fio-2.16

Starting 1 process

...

Run status group 0 (all jobs):

READ: io=2066.6MB, aggrb=169835KB/s, minb=169835KB/s, maxb=169835KB/s, mint=12457msec, maxt=12457msec

WRITE: io=2067.7MB, aggrb=169965KB/s, minb=169965KB/s, maxb=169965KB/s, mint=12457msec, maxt=12457msec

~166 MB/s, which is a bit better, but still not good…

Asking the community

Being desperate we decided to seek support from the Internet and posted our findings to the dm-crypt mailing list, but the response we got was not very encouraging:

If the numbers disturb you, then this is from lack of understanding on your side. You are probably unaware that encryption is a heavy-weight operation…

We decided to make a scientific research on this topic by typing “is encryption expensive” into Google Search and one of the top results, which actually contains meaningful measurements, is… our own post about cost of encryption, but in the context of TLS! This is a fascinating read on its own, but the gist is: modern crypto on modern hardware is very cheap even at Cloudflare scale (doing millions of encrypted HTTP requests per second). In fact, it is so cheap that Cloudflare was the first provider to offer free SSL/TLS for everyone.

Digging into the source code

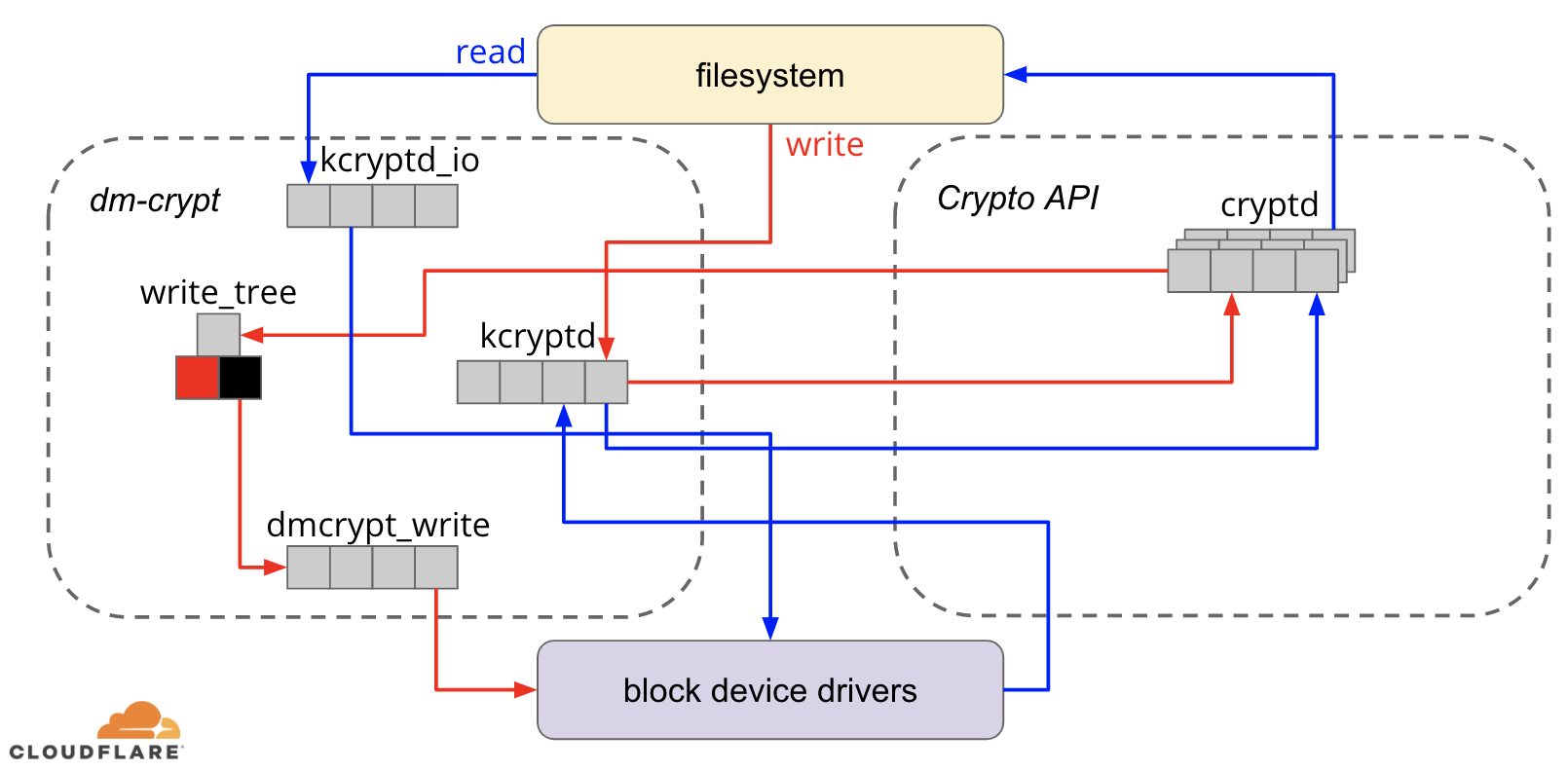

When trying to use the custom dm-crypt options described above we were curious why they exist in the first place and what is that “offloading” all about. Originally we expected dm-crypt to be a simple “proxy”, which just encrypts/decrypts data as it flows through the stack. Turns out dm-crypt does more than just encrypting memory buffers and a (simplified) IO traverse path diagram is presented below:

When the file system issues a write request, dm-crypt does not process it immediately - instead it puts it into a workqueue named “kcryptd”. In a nutshell, a kernel workqueue just schedules some work (encryption in this case) to be performed at some later time, when it is more convenient. When “the time” comes, dm-crypt sends the request to Linux Crypto API for actual encryption. However, modern Linux Crypto API is asynchronous as well, so depending on which particular implementation your system will use, most likely it will not be processed immediately, but queued again for “later time”. When Linux Crypto API will finally do the encryption, dm-crypt may try to sort pending write requests by putting each request into a red-black tree. Then a separate kernel thread again at “some time later” actually takes all IO requests in the tree and sends them down the stack.

Now for read requests: this time we need to get the encrypted data first from the hardware, but dm-crypt does not just ask for the driver for the data, but queues the request into a different workqueue named “kcryptd_io”. At some point later, when we actually have the encrypted data, we schedule it for decryption using the now familiar “kcryptd” workqueue. “kcryptd” will send the request to Linux Crypto API, which may decrypt the data asynchronously as well.

To be fair the request does not always traverse all these queues, but the important part here is that write requests may be queued up to 4 times in dm-crypt and read requests up to 3 times. At this point we were wondering if all this extra queueing can cause any performance issues. For example, there is a nice presentation from Google about the relationship between queueing and tail latency. One key takeaway from the presentation is:

A significant amount of tail latency is due to queueing effects

So, why are all these queues there and can we remove them?

Git archeology

No-one writes more complex code just for fun, especially for the OS kernel. So all these queues must have been put there for a reason. Luckily, the Linux kernel source is managed by git, so we can try to retrace the changes and the decisions around them.

The “kcryptd” workqueue was in the source since the beginning of the available history with the following comment:

Needed because it would be very unwise to do decryption in an interrupt context, so bios returning from read requests get queued here.

So it was for reads only, but even then - why do we care if it is interrupt context or not, if Linux Crypto API will likely use a dedicated thread/queue for encryption anyway? Well, back in 2005 Crypto API was not asynchronous, so this made perfect sense.

In 2006 dm-crypt started to use the “kcryptd” workqueue not only for encryption, but for submitting IO requests:

This patch is designed to help dm-crypt comply with the new constraints imposed by the following patch in -mm: md-dm-reduce-stack-usage-with-stacked-block-devices.patch

It seems the goal here was not to add more concurrency, but rather reduce kernel stack usage, which makes sense again as the kernel has a common stack across all the code, so it is a quite limited resource. It is worth noting, however, that the Linux kernel stack has been expanded in 2014 for x86 platforms, so this might not be a problem anymore.

A first version of “kcryptd_io” workqueue was added in 2007 with the intent to avoid:

starvation caused by many requests waiting for memory allocation…

The request processing was bottlenecking on a single workqueue here, so the solution was to add another one. Makes sense.

We are definitely not the first ones experiencing performance degradation because of extensive queueing: in 2011 a change was introduced to conditionally revert some of the queueing for read requests:

If there is enough memory, code can directly submit bio instead queuing this operation in a separate thread.

Unfortunately, at that time Linux kernel commit messages were not as verbose as today, so there is no performance data available.

In 2015 dm-crypt started to sort writes in a separate “dmcrypt_write” thread before sending them down the stack:

On a multiprocessor machine, encryption requests finish in a different order than they were submitted. Consequently, write requests would be submitted in a different order and it could cause severe performance degradation.

It does make sense as sequential disk access used to be much faster than the random one and dm-crypt was breaking the pattern. But this mostly applies to spinning disks, which were still dominant in 2015. It may not be as important with modern fast SSDs (including NVME SSDs).

Another part of the commit message is worth mentioning:

…in particular it enables IO schedulers like CFQ to sort more effectively…

It mentions the performance benefits for the CFQ IO scheduler, but Linux schedulers have improved since then to the point that CFQ scheduler has been removed from the kernel in 2018.

The same patchset replaces the sorting list with a red-black tree:

In theory the sorting should be performed by the underlying disk scheduler, however, in practice the disk scheduler only accepts and sorts a finite number of requests. To allow the sorting of all requests, dm-crypt needs to implement its own sorting.

The overhead associated with rbtree-based sorting is considered negligible so it is not used conditionally.

All that make sense, but it would be nice to have some backing data.

Interestingly, in the same patchset we see the introduction of our familiar “submit_from_crypt_cpus” option:

There are some situations where offloading write bios from the encryption threads to a single thread degrades performance significantly

Overall, we can see that every change was reasonable and needed, however things have changed since then:

- hardware became faster and smarter

- Linux resource allocation was revisited

- coupled Linux subsystems were rearchitected

And many of the design choices above may not be applicable to modern Linux.

The “clean-up”

Based on the research above we decided to try to remove all the extra queueing and asynchronous behaviour and revert dm-crypt to its original purpose: simply encrypt/decrypt IO requests as they pass through. But for the sake of stability and further benchmarking we ended up not removing the actual code, but rather adding yet another dm-crypt option, which bypasses all the queues/threads, if enabled. The flag allows us to switch between the current and new behaviour at runtime under full production load, so we can easily revert our changes should we see any side-effects. The resulting patch can be found on the Cloudflare GitHub Linux repository.

Synchronous Linux Crypto API

From the diagram above we remember that not all queueing is implemented in dm-crypt. Modern Linux Crypto API may also be asynchronous and for the sake of this experiment we want to eliminate queues there as well. What does “may be” mean, though? The OS may contain different implementations of the same algorithm (for example, hardware-accelerated AES-NI on x86 platforms and generic C-code AES implementations). By default the system chooses the “best” one based on the configured algorithm priority. dm-crypt allows overriding this behaviour and request a particular cipher implementation using the capi: prefix. However, there is one problem. Let us actually check the available AES-XTS (this is our disk encryption cipher, remember?) implementations on our system:

$ grep -A 11 'xts(aes)' /proc/crypto

name : xts(aes)

driver : xts(ecb(aes-generic))

module : kernel

priority : 100

refcnt : 7

selftest : passed

internal : no

type : skcipher

async : no

blocksize : 16

min keysize : 32

max keysize : 64

--

name : __xts(aes)

driver : cryptd(__xts-aes-aesni)

module : cryptd

priority : 451

refcnt : 1

selftest : passed

internal : yes

type : skcipher

async : yes

blocksize : 16

min keysize : 32

max keysize : 64

--

name : xts(aes)

driver : xts-aes-aesni

module : aesni_intel

priority : 401

refcnt : 1

selftest : passed

internal : no

type : skcipher

async : yes

blocksize : 16

min keysize : 32

max keysize : 64

--

name : __xts(aes)

driver : __xts-aes-aesni

module : aesni_intel

priority : 401

refcnt : 7

selftest : passed

internal : yes

type : skcipher

async : no

blocksize : 16

min keysize : 32

max keysize : 64

We want to explicitly select a synchronous cipher from the above list to avoid queueing effects in threads, but the only two supported are xts(ecb(aes-generic)) (the generic C implementation) and __xts-aes-aesni (the x86 hardware-accelerated implementation). We definitely want the latter as it is much faster (we’re aiming for performance here), but it is suspiciously marked as internal (see internal: yes). If we check the source code:

Mark a cipher as a service implementation only usable by another cipher and never by a normal user of the kernel crypto API

So this cipher is meant to be used only by other wrapper code in the Crypto API and not outside it. In practice this means, that the caller of the Crypto API needs to explicitly specify this flag, when requesting a particular cipher implementation, but dm-crypt does not do it, because by design it is not part of the Linux Crypto API, rather an “external” user. We already patch the dm-crypt module, so we could as well just add the relevant flag. However, there is another problem with AES-NI in particular: x86 FPU. “Floating point” you say? Why do we need floating point math to do symmetric encryption which should only be about bit shifts and XOR operations? We don’t need the math, but AES-NI instructions use some of the CPU registers, which are dedicated to the FPU. Unfortunately the Linux kernel does not always preserve these registers in interrupt context for performance reasons (saving/restoring FPU is expensive). But dm-crypt may execute code in interrupt context, so we risk corrupting some other process data and we go back to “it would be very unwise to do decryption in an interrupt context” statement in the original code.

Our solution to address the above was to create another somewhat “smart” Crypto API module. This module is synchronous and does not roll its own crypto, but is just a “router” of encryption requests:

- if we can use the FPU (and thus AES-NI) in the current execution context, we just forward the encryption request to the faster, “internal”

__xts-aes-aesniimplementation (and we can use it here, because now we are part of the Crypto API) - otherwise, we just forward the encryption request to the slower, generic C-based

xts(ecb(aes-generic))implementation

Using the whole lot

Let’s walk through the process of using it all together. The first step is to grab the patches and recompile the kernel (or just compile dm-crypt and our xtsproxy modules).

Next, let’s restart our IO workload in a separate terminal, so we can make sure we can reconfigure the kernel at runtime under load:

$ sudo fio --filename=/dev/mapper/encrypted-ram0 --readwrite=readwrite --bs=4k --direct=1 --loops=1000000 --name=crypt

crypt: (g=0): rw=rw, bs=4K-4K/4K-4K/4K-4K, ioengine=psync, iodepth=1

fio-2.16

Starting 1 process

...

In the main terminal make sure our new Crypto API module is loaded and available:

$ sudo modprobe xtsproxy

$ grep -A 11 'xtsproxy' /proc/crypto

driver : xts-aes-xtsproxy

module : xtsproxy

priority : 0

refcnt : 0

selftest : passed

internal : no

type : skcipher

async : no

blocksize : 16

min keysize : 32

max keysize : 64

ivsize : 16

chunksize : 16

Reconfigure the encrypted disk to use our newly loaded module and enable our patched dm-crypt flag (we have to use low-level dmsetup tool as cryptsetup obviously is not aware of our modifications):

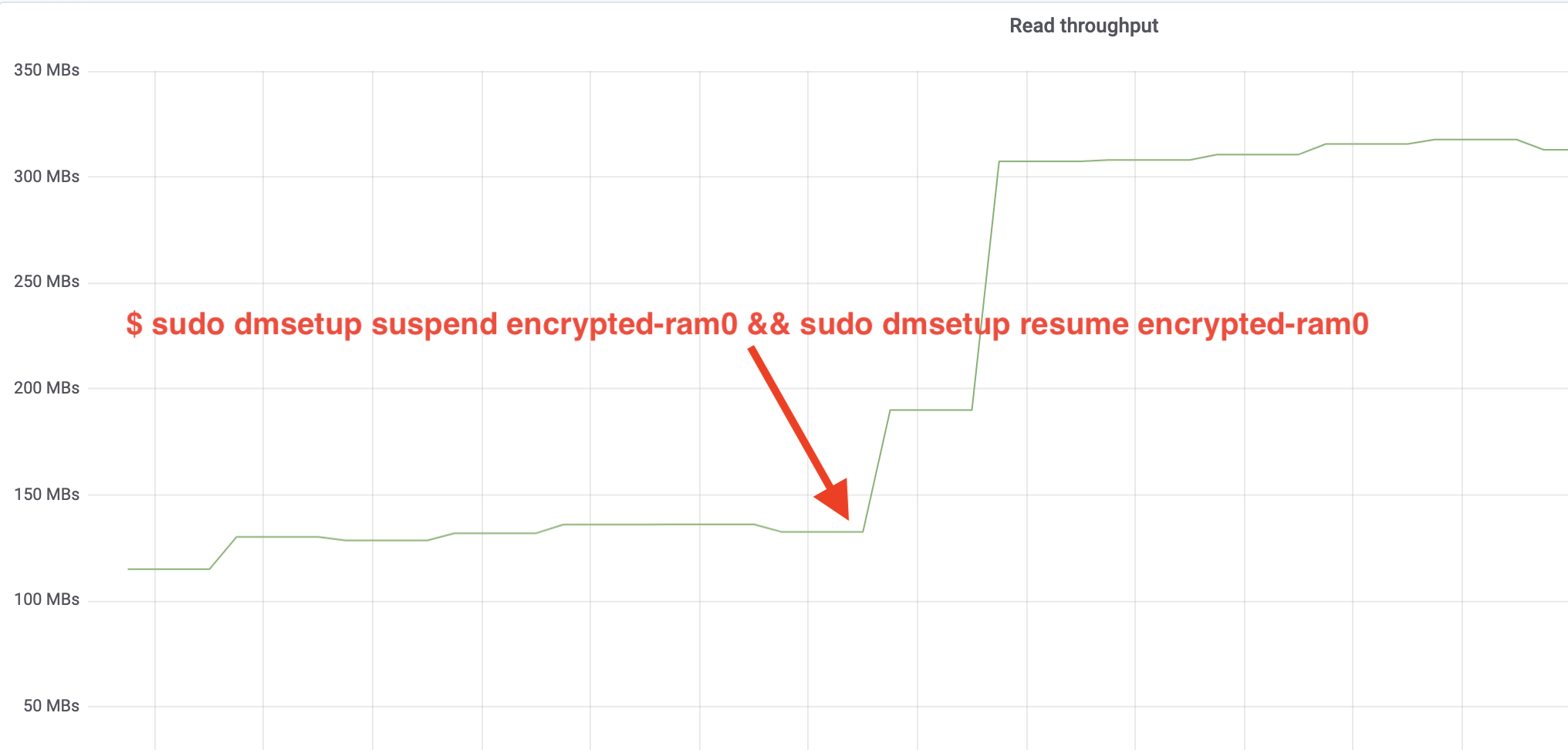

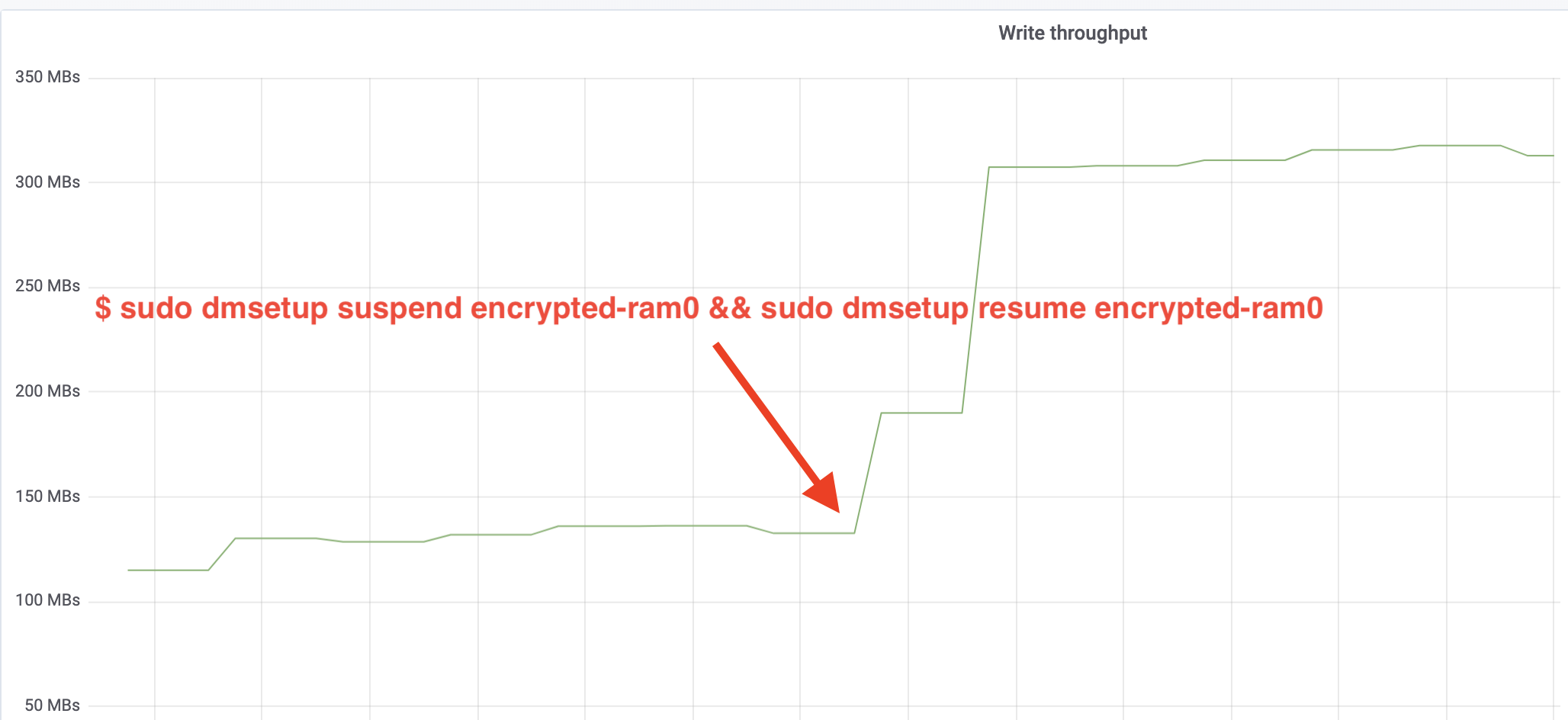

$ sudo dmsetup table encrypted-ram0 --showkeys | sed 's/aes-xts-plain64/capi:xts-aes-xtsproxy-plain64/' | sed 's/$/ 1 force_inline/' | sudo dmsetup reload encrypted-ram0

We just “loaded” the new configuration, but for it to take effect, we need to suspend/resume the encrypted device:

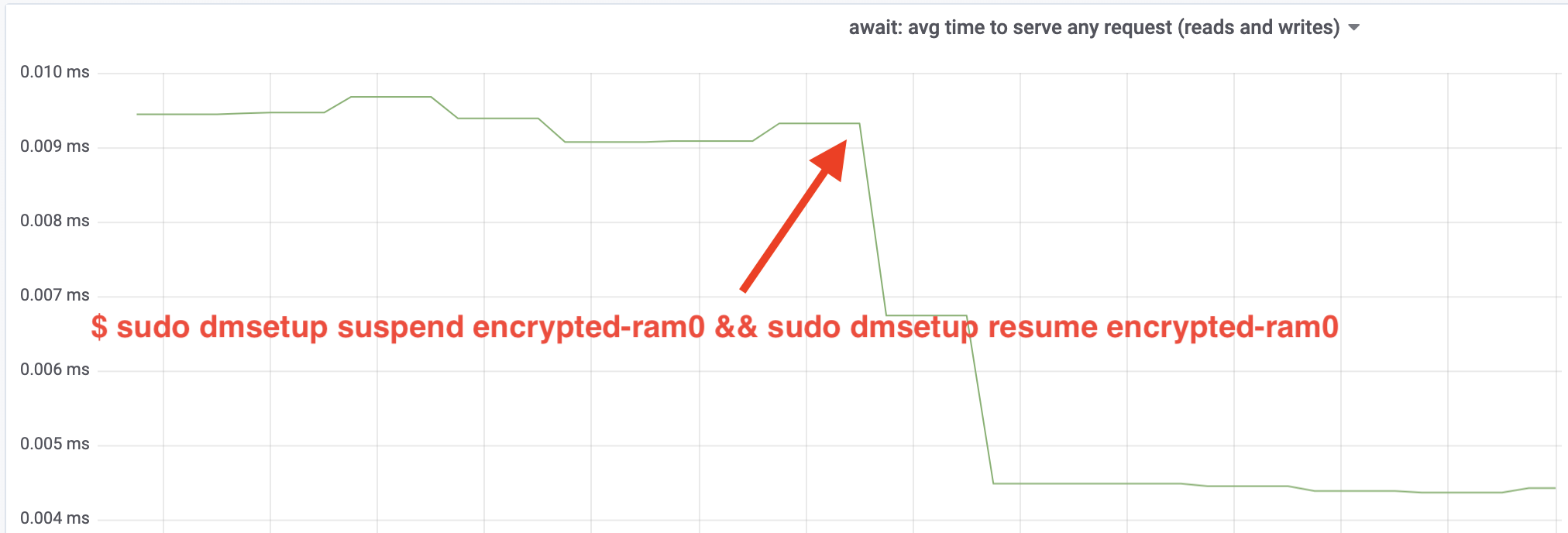

$ sudo dmsetup suspend encrypted-ram0 && sudo dmsetup resume encrypted-ram0

And now observe the result. We may go back to the other terminal running the fio job and look at the output, but to make things nicer, here’s a snapshot of the observed read/write throughput in Grafana:

Wow, we have more than doubled the throughput! With the total throughput of ~640 MB/s we’re now much closer to the expected ~696 MB/s from above. What about the IO latency? (The await statistic from the iostat reporting tool):

The latency has been cut in half as well!

To production

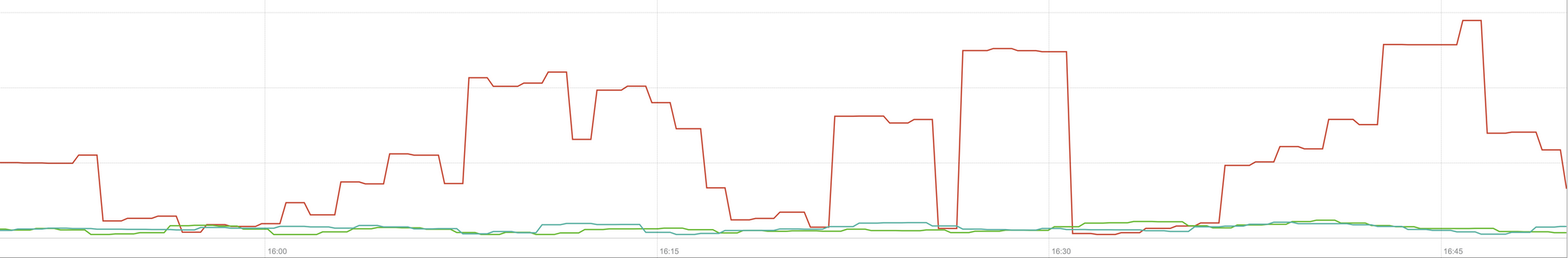

So far we have been using a synthetic setup with some parts of the full production stack missing, like file systems, real hardware and most importantly, production workload. To ensure we’re not optimising imaginary things, here is a snapshot of the production impact these changes bring to the caching part of our stack:

This graph represents a three-way comparison of the worst-case response times (99th percentile) for a cache hit in one of our servers. The green line is from a server with unencrypted disks, which we will use as baseline. The red line is from a server with encrypted disks with the default Linux disk encryption implementation and the blue line is from a server with encrypted disks and our optimisations enabled. As we can see the default Linux disk encryption implementation has a significant impact on our cache latency in worst case scenarios, whereas the patched implementation is indistinguishable from not using encryption at all. In other words the improved encryption implementation does not have any impact at all on our cache response speed, so we basically get it for free! That’s a win!

We’re just getting started

This post shows how an architecture review can double the performance of a system. Also we reconfirmed that modern cryptography is not expensive and there is usually no excuse not to protect your data.

We are going to submit this work for inclusion in the main kernel source tree, but most likely not in its current form. Although the results look encouraging we have to remember that Linux is a highly portable operating system: it runs on powerful servers as well as small resource constrained IoT devices and on many other CPU architectures as well. The current version of the patches just optimises disk encryption for a particular workload on a particular architecture, but Linux needs a solution which runs smoothly everywhere.

That said, if you think your case is similar and you want to take advantage of the performance improvements now, you may grab the patches and hopefully provide feedback. The runtime flag makes it easy to toggle the functionality on the fly and a simple A/B test may be performed to see if it benefits any particular case or setup. These patches have been running across our wide network of more than 200 data centres on five generations of hardware, so can be reasonably considered stable. Enjoy both performance and security from Cloudflare for all!

Update (October 11, 2020)

The main patch from this blog (in a slightly updated form) has been merged into mainline Linux kernel and is available since version 5.9 and onwards. The main difference is the mainline version exposes two flags instead of one, which provide the ability to bypass dm-crypt workqueues for reads and writes independently. For details, see the official dm-crypt documentation.