Passkb: how to reliably and securely bypass password paste blocking

These days passwords have to be really strong to withstand all modern passwords attacks. Not only passwords have to be long and complex, with all the data breaches around the world it is also very critical not to reuse the same password on several websites. As a result there is no way a human can memorize all the strong passwords for all the online services they need to access.

This is where password managers come into play: instead of memorising all the passwords we only need to remember one strong password and the password manager will remember the rest for us by storing our service passwords in an encrypted database. However, some websites try to make using a password manager particularly inconvenient by blocking the ability to paste passwords on their password input forms.

Why block password paste

Most websites, which block password paste, think they improve their security by doing so, when in fact they make it even worse, especially for their users. I will not list the details here, just recommend to read this although dated but still quite relevant post from Troy Hunt. In a nutshell, disabling paste on password input fields is just a “security theatre” and even some government organisations advise against it.

Unfortunately, though, not all website owners recognise the counter-reasons for blocking paste and still do it. This is very annoying, if you use a password manager, because passwords in a password manager are usually randomly generated and you have to somehow type each character by hand peeking on the password plaintext. And sometimes you can miss a character, fat finger or whatever and it is not immediately apparent where the typo is.

Unblocking password paste

There are many articles online (like this one) on how to restore paste functionality on password fields that block it. However, they boil down to two approaches:

- if you’re using Firefox, you can set

dom.event.clipboardevents.enabledtofalseinabout:config - on both Chrome and Firefox, you can install this (or any other similar) browser extension, which should unblock the paste functionality for you

But there are shortcomings of these approaches. First, they are browser dependent: what if you use Safari, Opera or MS Edge? Secondly, the idea behind both approaches is to somehow disable/rewrite some JavaScript on pages with password input fields, because paste blocking is usually implemented by this JavaScript. But this is a bit like “cracking a nut with a sledgehammer”, because modern Web applications extensively use JavaScript for many other primary functionality and just messing with it can potentially break the whole application.

Security considerations for browser extensions

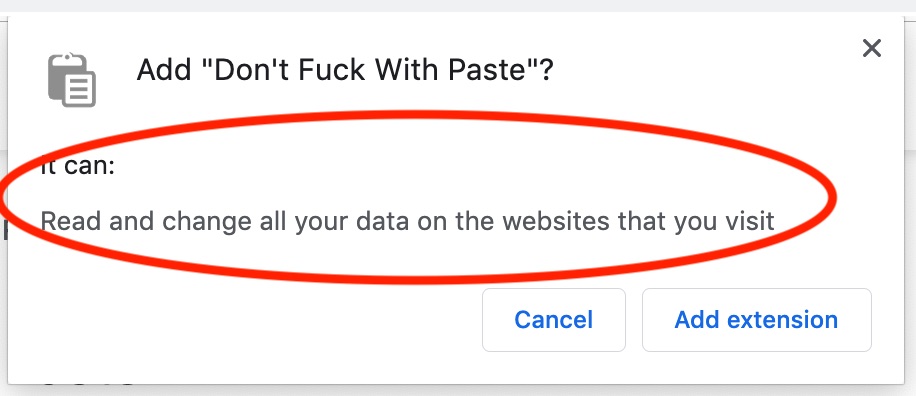

While a functionally broken Web application is a mere inconvenience, there are some security risks involved when using a browser extension to unblock password paste. For example, when you install this popular extension in Chrome, you get a warning like below:

Let’s reiterate: this extension would be able to read and modify all your browsing data on the fly. And this is not some kind of a bug, this is by design as the extension needs this functionality to do its job. Moreover, remember that browser extensions process the data after the TLS termination, so even if you browse HTTPS resources, these extensions still see full plaintext data. Finally, browser extensions run in the browser’s context - a process with full network access, so these extensions not only see all your browsing data, but can potentially leak it over the network. What could go wrong?

Just to be clear, I’m not implying that all these extensions are evil by design. Most of them are even open-source and you can check that the author’s intention is indeed only to unblock password paste functionality and nothing else. However, it is the environment that is risky: browser extensions (like the Web applications themselves) are mostly written in JavaScript. And in JavaScript ecosystem developers tend to heavily rely on NPM registry (and similar code repositories) for their code dependencies. However, sometimes these dependencies themselves may become compromised (for example, due to the maintainers’ account takeover/hijack), thus all dependent projects suddenly start distributing potentially malicious code. And on top of that, as we’ve learned above, this code runs in a privileged context having full access to your browsing data and the Internet.

Rethinking paste unblock

Let’s zoom out for a bit and take a look at the current paste unblock methods. From a high-level perspective they follow the same path: we know that password paste blocking is implemented via some JavaScript code in the Web application and the above mentioned methods try to somehow neutralise or break this code.

What if we take a different approach? Instead of trying to disable the paste blocking code we will just present the password input in the form the Web application expects - by typing it in. However, the typing doesn’t have to be performed by the operator - we can have a program, which will instruct the operating system to type the complex password on our behalf. The ability to simulate keystrokes exists in modern operating systems for a while now to support different accessibility applications, virtual keyboards, voice input etc. So why not use it to our advantage and “ask” the operating system to type a password for us (if it is otherwise cumbersome to type manually)?

Introducing passkb

Passkb is a simple command line application, which helps to type complex passwords. The workflow is pretty simple: if you encounter a Web application, which blocks password paste, you can paste your password into passkb and passkb will type it in for you:

We don’t need to run third-party browser extensions or mess with browser settings anymore - this approach works for every browser and for any Web application. Moreover, because passkb emulates typing, Web applications can never block it, as they have to allow typing by design. Another notable security advantage is that passkb runs as a separate process in the operating system, so it can be easily sandboxed and denied network access (after all, we’re trusting it with our passwords). The only downside is that there is a slight inconvenience of switching several windows to “copy-type” a password and you have to do it in a timely manner: by default you have 5 seconds (but it is configurable) to put the cursor in the right place for the tool to type the password in the needed form. Otherwise, it will type the password to wherever the cursor and the focus currently is.

Linux specifics

While on both Windows and Mac OS passkb uses standard APIs to generate typing events, Linux may require some additional config to make the tool usable. On Linux the tool uses the special /dev/uinput device, thus it has to be present in the system. Most popular Linux distributions already support this special device file (although you might have to run modprobe uinput), but if you compile your own kernel, make sure to enable CONFIG_INPUT_UINPUT in the kernel configuration file.

Additionally, to generate typing events through this interface the process needs read/write access for /dev/uinput. However, by default, only the root user is allowed to read and write to the file. Probably, the best way to reconfigure this is:

- create a dedicated group

- change the group ownership of the

/dev/uinputto our newly created group - change the access bits on

/dev/uinputto660(group can read/write as well) - add yourself (and any other system users, who would use the tool) to the group

And remember: permission and ownership changes to the device filesystem do not persist, so will reset on reboot. You need some kind of a startup script or a systemd udev rule to adjust the ownership and the permission bits of /dev/uinput on each boot.

Potential future improvements

It would be nice to improve the user experience of the tool and not to confine the user to 5 seconds (or any other timeout) to type the password in the correct place. One way to do so is to figure out, if some keyboard shortcuts could be registered for the tool, which can trigger the typing of the provided password. This way the user may have the familiar experience of Ctrl/Cmd+C/Ctrl/Cmd+V, but Ctrl/Cmd+V may be replaced by some other key combo and will type the password instead of pasting it. If you have any ideas on how to implement this, pull requests are welcome.