How to execute an object file: Part 1

Calling a simple function without linking

This is a repost of my post from the Cloudflare Blog

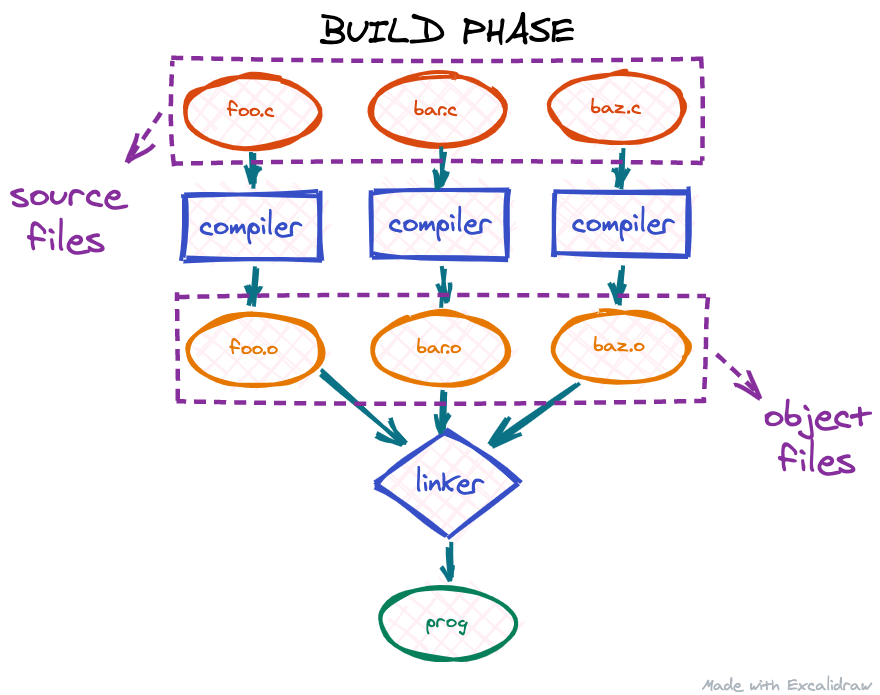

When we write software using a high-level compiled programming language, there are usually a number of steps involved in transforming our source code into the final executable binary:

First, our source files are compiled by a compiler translating the high-level programming language into machine code. The output of the compiler is a number of object files. If the project contains multiple source files, we usually get as many object files. The next step is the linker: since the code in different object files may reference each other, the linker is responsible for assembling all these object files into one big program and binding these references together. The output of the linker is usually our target executable, so only one file.

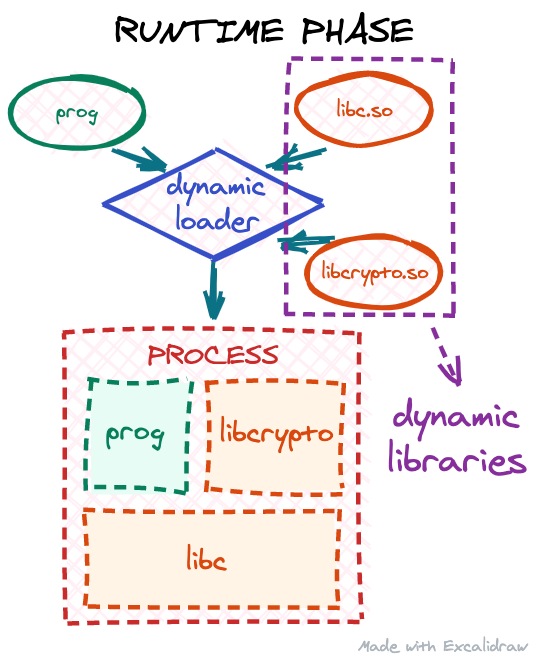

However, at this point, our executable might still be incomplete. These days, most executables on Linux are dynamically linked: the executable itself does not have all the code it needs to run a program. Instead it expects to “borrow” part of the code at runtime from shared libraries for some of its functionality:

This process is called runtime linking: when our executable is being started, the operating system will invoke the dynamic loader, which should find all the needed libraries, copy/map their code into our target process address space, and resolve all the dependencies our code has on them.

One interesting thing to note about this overall process is that we get the executable machine code directly from step 1 (compiling the source code), but if any of the later steps fail, we still can’t execute our program. So, in this series of blog posts we will investigate if it is possible to execute machine code directly from object files skipping all the later steps.

Why would we want to execute an object file?

There may be many reasons. Perhaps we’re writing an open-source replacement for a proprietary Linux driver or an application, and want to compare if the behaviour of some code is the same. Or we have a piece of a rare, obscure program and we can’t link to it, because it was compiled with a rare, obscure compiler. Maybe we have a source file, but cannot create a full featured executable, because of the missing build time or runtime dependencies. Malware analysis, code from a different operating system etc - all these scenarios may put us in a position, where either linking is not possible or the runtime environment is not suitable.

A simple toy object file

For the purposes of this article, let’s create a simple toy object file, so we can use it in our experiments:

obj.c:

int add5(int num)

{

return num + 5;

}

int add10(int num)

{

return num + 10;

}

Our source file contains only 2 functions, add5 and add10, which adds 5 or 10 respectively to the only input parameter. It’s a small but fully functional piece of code, and we can easily compile it into an object file:

$ gcc -c obj.c

$ ls

obj.c obj.o

Loading an object file into the process memory

Now we will try to import the add5 and add10 functions from the object file and execute them. When we talk about executing an object file, we mean using an object file as some sort of a library. As we learned above, when we have an executable that utilises external shared libraries, the dynamic loader loads these libraries into the process address space for us. With object files, however, we have to do this manually, because ultimately we can’t execute machine code that doesn’t reside in the operating system’s RAM. So, to execute object files we still need some kind of a wrapper program:

loader.c:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

static void load_obj(void)

{

/* load obj.o into memory */

}

static void parse_obj(void)

{

/* parse an object file and find add5 and add10 functions */

}

static void execute_funcs(void)

{

/* execute add5 and add10 with some inputs */

}

int main(void)

{

load_obj();

parse_obj();

execute_funcs();

return 0;

}

Above is a self-contained object loader program with some functions as placeholders. We will be implementing these functions (and adding more) in the course of this post.

First, as we established already, we need to load our object file into the process address space. We could just read the whole file into a buffer, but that would not be very efficient. Real-world object files might be big, but as we will see later, we don’t need all of the object’s file contents. So it is better to mmap the file instead: this way the operating system will lazily read the parts from the file we need at the time we need them. Let’s implement the load_obj function:

loader.c:

...

/* for open(2), fstat(2) */

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

/* for close(2), fstat(2) */

#include <unistd.h>

/* for mmap(2) */

#include <sys/mman.h>

/* parsing ELF files */

#include <elf.h>

/* for errno */

#include <errno.h>

typedef union {

const Elf64_Ehdr *hdr;

const uint8_t *base;

} objhdr;

/* obj.o memory address */

static objhdr obj;

static void load_obj(void)

{

struct stat sb;

int fd = open("obj.o", O_RDONLY);

if (fd <= 0) {

perror("Cannot open obj.o");

exit(errno);

}

/* we need obj.o size for mmap(2) */

if (fstat(fd, &sb)) {

perror("Failed to get obj.o info");

exit(errno);

}

/* mmap obj.o into memory */

obj.base = mmap(NULL, sb.st_size, PROT_READ, MAP_PRIVATE, fd, 0);

if (obj.base == MAP_FAILED) {

perror("Maping obj.o failed");

exit(errno);

}

close(fd);

}

...

If we don’t encounter any errors, after load_obj executes we should get the memory address, which points to the beginning of our obj.o in the obj global variable. It is worth noting we have created a special union type for the obj variable: we will be parsing obj.o later (and peeking ahead - object files are actually ELF files), so will be referring to the address both as Elf64_Ehdr (ELF header structure in C) and a byte pointer (parsing ELF files involves calculations of byte offsets from the beginning of the file).

A peek inside an object file

To use some code from an object file, we need to find it first. As I’ve leaked above, object files are actually ELF files (the same format as Linux executables and shared libraries) and luckily they’re easy to parse on Linux with the help of the standard elf.h header, which includes many useful definitions related to the ELF file structure. But we actually need to know what we’re looking for, so a high-level understanding of an ELF file is needed.

ELF segments and sections

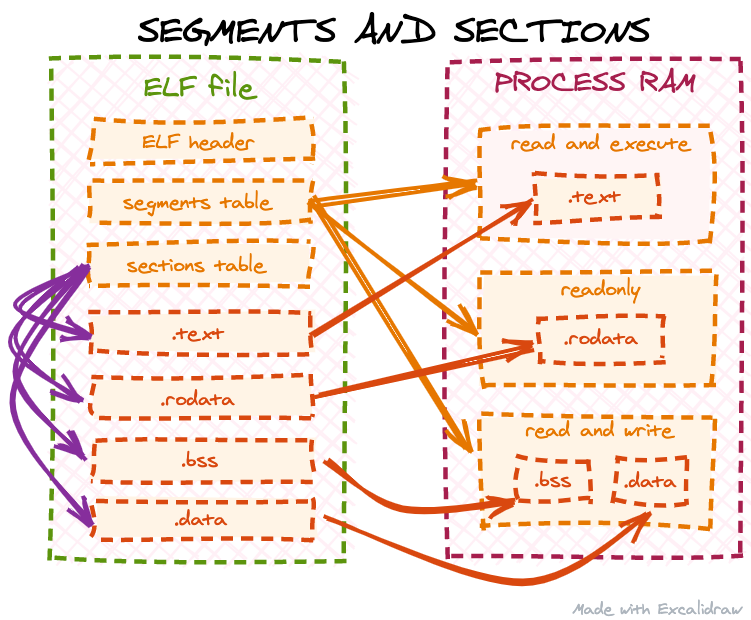

Segments (also known as program headers) and sections are probably the main parts of an ELF file and usually a starting point of any ELF tutorial. However, there is often some confusion between the two. Different sections contain different types of ELF data: executable code (which we are most interested in in this post), constant data, global variables etc. Segments, on the other hand, do not contain any data themselves - they just describe to the operating system how to properly load sections into RAM for the executable to work correctly. Some tutorials say “a segment may include 0 or more sections”, which is not entirely accurate: segments do not contain sections, rather they just indicate to the OS where in memory a particular section should be loaded and what is the access pattern for this memory (read, write or execute):

Furthermore, object files do not contain any segments at all: an object file is not meant to be directly loaded by the OS. Instead, it is assumed it will be linked with some other code, so ELF segments are usually generated by the linker, not the compiler. We can check this by using the readelf command:

$ readelf --segments obj.o

There are no program headers in this file.

Object file sections

The same readelf command can be used to get all the sections from our object file:

$ readelf --sections obj.o

There are 11 section headers, starting at offset 0x268:

Section Headers:

[Nr] Name Type Address Offset

Size EntSize Flags Link Info Align

[ 0] NULL 0000000000000000 00000000

0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0 0 0

[ 1] .text PROGBITS 0000000000000000 00000040

000000000000001e 0000000000000000 AX 0 0 1

[ 2] .data PROGBITS 0000000000000000 0000005e

0000000000000000 0000000000000000 WA 0 0 1

[ 3] .bss NOBITS 0000000000000000 0000005e

0000000000000000 0000000000000000 WA 0 0 1

[ 4] .comment PROGBITS 0000000000000000 0000005e

000000000000001d 0000000000000001 MS 0 0 1

[ 5] .note.GNU-stack PROGBITS 0000000000000000 0000007b

0000000000000000 0000000000000000 0 0 1

[ 6] .eh_frame PROGBITS 0000000000000000 00000080

0000000000000058 0000000000000000 A 0 0 8

[ 7] .rela.eh_frame RELA 0000000000000000 000001e0

0000000000000030 0000000000000018 I 8 6 8

[ 8] .symtab SYMTAB 0000000000000000 000000d8

00000000000000f0 0000000000000018 9 8 8

[ 9] .strtab STRTAB 0000000000000000 000001c8

0000000000000012 0000000000000000 0 0 1

[10] .shstrtab STRTAB 0000000000000000 00000210

0000000000000054 0000000000000000 0 0 1

Key to Flags:

W (write), A (alloc), X (execute), M (merge), S (strings), I (info),

L (link order), O (extra OS processing required), G (group), T (TLS),

C (compressed), x (unknown), o (OS specific), E (exclude),

l (large), p (processor specific)

There are different tutorials online describing the most popular ELF sections in detail. Another great reference is the Linux manpages project. It is handy because it describes both sections’ purpose as well as C structure definitions from elf.h, which makes it a one-stop shop for parsing ELF files. However, for completeness, below is a short description of the most popular sections one may encounter in an ELF file:

.text: this section contains the executable code (the actual machine code, which was created by the compiler from our source code). This section is the primary area of interest for this post as it should contain theadd5andadd10functions we want to use..dataand.bss: these sections contain global and static local variables. The difference is:.datahas variables with an initial value (defined likeint foo = 5;) and.bssjust reserves space for variables with no initial value (defined likeint bar;)..rodata: this section contains constant data (mostly strings or byte arrays). For example, if we use a string literal in the code (for example, forprintfor some error message), it will be stored here. Note, that.rodatais missing from the output above as we didn’t use any string literals or constant byte arrays inobj.c..symtab: this section contains information about the symbols in the object file: functions, global variables, constants etc. It may also contain information about external symbols the object file needs, like needed functions from the external libraries..strtaband.shstrtab: contain packed strings for the ELF file. Note, that these are not the strings we may define in our source code (those go to the.rodatasection). These are the strings describing the names of other ELF structures, like symbols from.symtabor even section names from the table above. ELF binary format aims to make its structures compact and of a fixed size, so all strings are stored in one place and the respective data structures just reference them as an offset in either.shstrtabor.strtabsections instead of storing the full string locally.

The .symtab section

At this point, we know that the code we want to import and execute is located in the obj.o’s .text section. But we have two functions, add5 and add10, remember? At this level the .text section is just a byte blob - how do we know where each of these functions is located? This is where the .symtab (the “symbol table”) comes in handy. It is so important that it has its own dedicated parameter in readelf:

$ readelf --symbols obj.o

Symbol table '.symtab' contains 10 entries:

Num: Value Size Type Bind Vis Ndx Name

0: 0000000000000000 0 NOTYPE LOCAL DEFAULT UND

1: 0000000000000000 0 FILE LOCAL DEFAULT ABS obj.c

2: 0000000000000000 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 1

3: 0000000000000000 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 2

4: 0000000000000000 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 3

5: 0000000000000000 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 5

6: 0000000000000000 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 6

7: 0000000000000000 0 SECTION LOCAL DEFAULT 4

8: 0000000000000000 15 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 1 add5

9: 000000000000000f 15 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 1 add10

Let’s ignore the other entries for now and just focus on the last two lines, because they conveniently have add5 and add10 as their symbol names. And indeed, this is the info about our functions. Apart from the names, the symbol table provides us with some additional metadata:

- The

Ndxcolumn tells us the index of the section, where the symbol is located. We can cross-check it with the section table above and confirm that indeed these functions are located in.text(section with the index1). Typebeing set toFUNCconfirms that these are indeed functions.Sizetells us the size of each function, but this information is not very useful in our context. The same goes forBindandVis.- Probably the most useful piece of information is

Value. The name is misleading, because it is actually an offset from the start of the containing section in this context. That is, theadd5function starts just from the beginning of.textandadd10is located from 15th byte and onwards.

So now we have all the pieces on how to parse an ELF file and find the functions we need.

Finding and executing a function from an object file

Given what we have learned so far, let’s define a plan on how to proceed to import and execute a function from an object file:

- Find the ELF sections table and

.shstrtabsection (we need.shstrtablater to lookup sections in the section table by name). - Find the

.symtaband.strtabsections (we need.strtabto lookup symbols by name in.symtab). - Find the

.textsection and copy it into RAM with executable permissions. - Find

add5andadd10function offsets from the.symtab. - Execute

add5andadd10functions.

Let’s start by adding some more global variables and implementing the parse_obj function:

loader.c:

...

/* sections table */

static const Elf64_Shdr *sections;

static const char *shstrtab = NULL;

/* symbols table */

static const Elf64_Sym *symbols;

/* number of entries in the symbols table */

static int num_symbols;

static const char *strtab = NULL;

...

static void parse_obj(void)

{

/* the sections table offset is encoded in the ELF header */

sections = (const Elf64_Shdr *)(obj.base + obj.hdr->e_shoff);

/* the index of `.shstrtab` in the sections table is encoded in the ELF header

* so we can find it without actually using a name lookup

*/

shstrtab = (const char *)(obj.base + sections[obj.hdr->e_shstrndx].sh_offset);

...

}

...

Now that we have references to both the sections table and the .shstrtab section, we can lookup other sections by their name. Let’s create a helper function for that:

loader.c:

...

static const Elf64_Shdr *lookup_section(const char *name)

{

size_t name_len = strlen(name);

/* number of entries in the sections table is encoded in the ELF header */

for (Elf64_Half i = 0; i < obj.hdr->e_shnum; i++) {

/* sections table entry does not contain the string name of the section

* instead, the `sh_name` parameter is an offset in the `.shstrtab`

* section, which points to a string name

*/

const char *section_name = shstrtab + sections[i].sh_name;

size_t section_name_len = strlen(section_name);

if (name_len == section_name_len && !strcmp(name, section_name)) {

/* we ignore sections with 0 size */

if (sections[i].sh_size)

return sections + i;

}

}

return NULL;

}

...

Using our new helper function, we can now find the .symtab and .strtab sections:

loader.c:

...

static void parse_obj(void)

{

...

/* find the `.symtab` entry in the sections table */

const Elf64_Shdr *symtab_hdr = lookup_section(".symtab");

if (!symtab_hdr) {

fputs("Failed to find .symtab\n", stderr);

exit(ENOEXEC);

}

/* the symbols table */

symbols = (const Elf64_Sym *)(obj.base + symtab_hdr->sh_offset);

/* number of entries in the symbols table = table size / entry size */

num_symbols = symtab_hdr->sh_size / symtab_hdr->sh_entsize;

const Elf64_Shdr *strtab_hdr = lookup_section(".strtab");

if (!strtab_hdr) {

fputs("Failed to find .strtab\n", stderr);

exit(ENOEXEC);

}

strtab = (const char *)(obj.base + strtab_hdr->sh_offset);

...

}

...

Next, let’s focus on the .text section. We noted earlier in our plan that it is not enough to just locate the .text section in the object file, like we did with other sections. We would need to copy it over to a different location in RAM with executable permissions. There are several reasons for that, but these are the main ones:

- Many CPU architectures either don’t allow execution of the machine code, which is unaligned in memory (4 kilobytes for x86 systems), or they execute it with a performance penalty. However, the

.textsection in an ELF file is not guaranteed to be positioned at a page aligned offset, because the on-disk version of the ELF file aims to be compact rather than convenient. - We may need to modify some bytes in the

.textsection to perform relocations (we don’t need to do it in this case, but will be dealing with relocations in future posts). If, for example, we forget to use theMAP_PRIVATEflag, when mapping the ELF file, our modifications may propagate to the underlying file and corrupt it. - Finally, different sections, which are needed at runtime, like

.text,.data,.bssand.rodata, require different memory permission bits: the.textsection memory needs to be both readable and executable, but not writable (it is considered a bad security practice to have memory both writable and executable). The.dataand.bsssections need to be readable and writable to support global variables, but not executable. The.rodatasection should be readonly, because its purpose is to hold constant data. To support this, each section must be allocated on a page boundary as we can only set memory permission bits on whole pages and not custom ranges. Therefore, we need to create new, page aligned memory ranges for these sections and copy the data there.

To create a page aligned copy of the .text section, first we actually need to know the page size. Many programs usually just hardcode the page size to 4096 (4 kilobytes), but we shouldn’t rely on that. While it’s accurate for most x86 systems, other CPU architectures, like arm64, might have a different page size. So hard coding a page size may make our program non-portable. Let’s find the page size and store it in another global variable:

loader.c:

...

static uint64_t page_size;

static inline uint64_t page_align(uint64_t n)

{

return (n + (page_size - 1)) & ~(page_size - 1);

}

...

static void parse_obj(void)

{

...

/* get system page size */

page_size = sysconf(_SC_PAGESIZE);

...

}

...

Notice, we have also added a convenience function page_align, which will round up the passed in number to the next page aligned boundary. Next, back to the .text section. As a reminder, we need to:

- Find the

.textsection metadata in the sections table. - Allocate a chunk of memory to hold the

.textsection copy. - Actually copy the

.textsection to the newly allocated memory. - Make the

.textsection executable, so we can later call functions from it.

Here is the implementation of the above steps:

loader.c:

...

/* runtime base address of the imported code */

static uint8_t *text_runtime_base;

...

static void parse_obj(void)

{

...

/* find the `.text` entry in the sections table */

const Elf64_Shdr *text_hdr = lookup_section(".text");

if (!text_hdr) {

fputs("Failed to find .text\n", stderr);

exit(ENOEXEC);

}

/* allocate memory for `.text` copy rounding it up to whole pages */

text_runtime_base = mmap(NULL, page_align(text_hdr->sh_size), PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE | MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0);

if (text_runtime_base == MAP_FAILED) {

perror("Failed to allocate memory for .text");

exit(errno);

}

/* copy the contents of `.text` section from the ELF file */

memcpy(text_runtime_base, obj.base + text_hdr->sh_offset, text_hdr->sh_size);

/* make the `.text` copy readonly and executable */

if (mprotect(text_runtime_base, page_align(text_hdr->sh_size), PROT_READ | PROT_EXEC)) {

perror("Failed to make .text executable");

exit(errno);

}

}

...

Now we have all the pieces we need to locate the address of a function. Let’s write a helper for it:

loader.c:

...

static void *lookup_function(const char *name)

{

size_t name_len = strlen(name);

/* loop through all the symbols in the symbol table */

for (int i = 0; i < num_symbols; i++) {

/* consider only function symbols */

if (ELF64_ST_TYPE(symbols[i].st_info) == STT_FUNC) {

/* symbol table entry does not contain the string name of the symbol

* instead, the `st_name` parameter is an offset in the `.strtab`

* section, which points to a string name

*/

const char *function_name = strtab + symbols[i].st_name;

size_t function_name_len = strlen(function_name);

if (name_len == function_name_len && !strcmp(name, function_name)) {

/* st_value is an offset in bytes of the function from the

* beginning of the `.text` section

*/

return text_runtime_base + symbols[i].st_value;

}

}

}

return NULL;

}

...

And finally we can implement the execute_funcs function to import and execute code from an object file:

loader.c:

...

static void execute_funcs(void)

{

/* pointers to imported add5 and add10 functions */

int (*add5)(int);

int (*add10)(int);

add5 = lookup_function("add5");

if (!add5) {

fputs("Failed to find add5 function\n", stderr);

exit(ENOENT);

}

puts("Executing add5...");

printf("add5(%d) = %d\n", 42, add5(42));

add10 = lookup_function("add10");

if (!add10) {

fputs("Failed to find add10 function\n", stderr);

exit(ENOENT);

}

puts("Executing add10...");

printf("add10(%d) = %d\n", 42, add10(42));

}

...

Let’s compile our loader and make sure it works as expected:

$ gcc -o loader loader.c

$ ./loader

Executing add5...

add5(42) = 47

Executing add10...

add10(42) = 52

Voila! We have successfully imported code from obj.o and executed it. Of course, the example above is simplified: the code in the object file is self-contained, does not reference any global variables or constants, and does not have any external dependencies. In future posts we will look into more complex code and how to handle such cases.

Security considerations

Processing external inputs, like parsing an ELF file from the disk above, should be handled with care. The code from loader.c omits a lot of bounds checking and additional ELF integrity checks, when parsing the object file. The code is simplified for the purposes of this post, but most likely not production ready, as it can probably be exploited by specifically crafted malicious inputs. Use it only for educational purposes!

The complete source code from this post can be found here.